Introduction

The past few years have seen growing maritime security challenges intersect with rising geopolitical competition in the world in general and the Indo-Pacific in particular. China’s gray zone coercion is challenging the maritime order. The US and its partners are building coalitions like the Quad and developing countries are seeing tensions in areas like subsea cables. Southeast Asia, the world’s fifth-largest economy and third-most populous actor, sits at the center of these dynamics and is central to their trajectory. Located at the heart of the Indo-Pacific region, Southeast Asia is on the front lines of China’s maritime assertiveness in the South China Sea, while the Malacca Straits accounts for at least a third of global trade. The resulting dynamics will be critical to US interests. The state of the emerging regional maritime order will help shape norms and the balance of power across the Indo-Pacific.

This policy brief explores the intersection between Indo-Pacific strategic competition and maritime security in Southeast Asia. It is informed by conversations with policymakers and experts across all 11 countries in Southeast Asia and field research to regional capitals. This brief makes three arguments:

- First, intensifying major power competition adds to a growing list of comprehensive issues Southeast Asian governments are facing in the maritime domain. These are visible across six realms: political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental. They include subsea cables, sustainable blue economy management and maritime disputes.

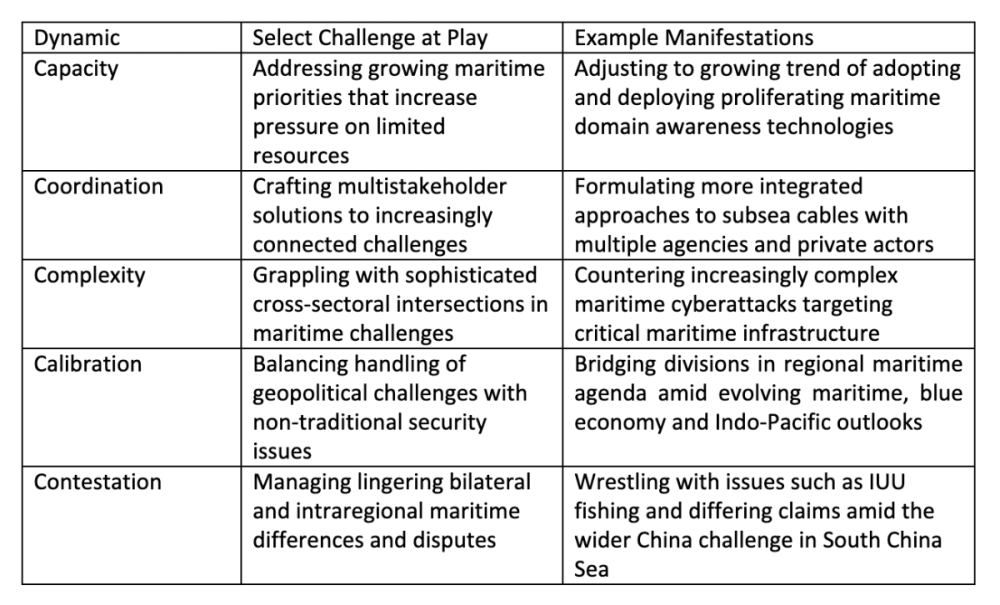

- Second, the intersection of strategic competition and maritime security issues is producing additional challenging dynamics for Southeast Asian states. Five areas are especially notable: capacity; coordination; complexity; calibration and contestation. These touch on areas such as maritime domain awareness technologies, maritime cyberattacks and the advancement of maritime and Indo-Pacific outlooks in in Southeast Asia and ASEAN.

- Third and finally, actors, including regional states as well as the US and its partners, can help Southeast Asian efforts to advance a shared vision of an open maritime order conducive to development and security. Particular focus should be placed on advancing collaboration in areas such as underwater domain awareness, critical maritime infrastructure, capacity-building and economic security.

Southeast Asia Maritime Security and Indo-Pacific Competition

The current period of intensified competition is just the latest phase in the evolution of maritime security in Southeast Asia within the wider regional and global landscape. The enduring regional centrality of the maritime domain is captured by the fact that nearly half of its countries rank among the world’s top 50 largest coastlines by one count. Some facets of conversations today date back centuries, be it the role of maritime powers chronicled by strategists like Alfred Thayer Mahan or the notion of free seas embedded in mare liberum advanced by Hugo Grotius. In Southeast Asia, the age of decolonization following World War II saw a wider range of states engaging in opportunities and challenges offered by the maritime domain amid technological advances. These trends continued amid other developments such as Cold War tensions and legal debates such as on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which featured prominent regional practitioners such as Singapore’s Tommy Koh and Indonesia’s Hasjim Djalal.

The maritime security paradigm gained more traction in Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific in the post-Cold War period during a period of rising threats and broadening notions of security in the 1990s and 2000s. During this period, growing incidences of piracy led to the formation of minilateral Malacca Straits Patrols alongside the intensified global focus on terrorism following the September 11 attacks. Tragic incidents like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami were also reminders of the interconnected nature of the Indo-Pacific, birthing new institutions like the Quad, alongside subsequent development of regional information sharing centers like the Information Fusion Center set up in 2009 in Singapore. Cumulatively, these developments broadened the aperture of maritime security but also intensified government workloads and multistakeholder concerns.

The 2010 and 2020s have seen an intensification of strategic competition add to a long list of challenges Southeast Asian states face. US-China competition has seeped into the South China Sea, spotlighted lingering intraregional disputes and complicated geoeconomic opportunities in blue economy-related areas like ports and subsea cables. At the same time, the region also has a comprehensive set of wider maritime security challenges. Several states top global risk indicators in areas such as illegal fishing, marine debris and rising sea levels. Periodic developments like the flow of maritime refugees and treatment of so-called sea nomads have pointed to persistent issues amid the ebbs and flows on other trends like piracy and terrorism. Southeast Asia’s challenges are visible across six key realms: political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental. These can be categorized by employing the PESTLE framework at times used in business analysis.

Evolving Dynamics in Maritime Security in Southeast Asia

The intersection of intensified competition and maritime security contributes to several strategic dynamics that affect calculations of key actors. Dynamics are notable across five areas: capacity; coordination; complexity; calibration and contestation. These can be described through a “5C framework” below.

The first is capacity. Intensifying competition has both reinforced the need for and complicated the dynamics of boosting state capacity. One notable instance is in maritime domain awareness (MDA). The needs here are vast despite regional trends like the expansion of coast guard forces. To take just one example, Philippine officials have publicly disclosed that the number of Chinese vessels around its waters in just one single week – including navy, coast guard and maritime militia – have at times run up into the hundreds. The past few years has seen a proliferation of capacity-building technology offers from major powers to states such as Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam. These include the European Union’s IORIS, the Quad’s Indo-Pacific Partnership For Maritime Domain Awareness and Canada’s Dark Vessel platform. Yet officials also privately say that challenges remain on various fronts in terms of adoption and usage, including compatibility. These limits are important to recognize because domain awareness involves not just receiving data, but also understanding how it connects to analysis and rapid action.

The second is coordination. The spillover of competitive dynamics into the economic realm has intensified already challenging stakeholder coordination dynamics. One example is subsea cables. These cables carry around 99 percent of the world’s data traffic and see breaches nearly every other day – mostly natural but at times allegedly intentional as seen off of Taiwan’s coast or in the Baltic Sea. They can require weeks or months to fix. Southeast Asian governments recognize the risks in this domain. Countries like Vietnam have seen multiple cables disrupted simultaneously, and ASEAN has taken basic steps such as streamlining the permitting application process for cable repair. But officials say a coordinated approach across key areas – including cable planning, ownership, resilience and maintenance – has thus far proven elusive as it requires synchronization across diverse government agencies and private actors.

The third is complexity. Competition has inserted another element of complexity as states grapple with more cross-sectoral and multilayered maritime challenges. One case in point is maritime cyberattacks. State- and non-state maritime cyberattacks targeting ships and ports have recorded up to triple digit percentage rises over the past few years, with one estimate suggesting that a single major coordinated attack on Asian ports could cost over $100 billion in losses. Some Southeast Asian governments such as Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand have acknowledged the role of critical information infrastructure in cyber approaches that includes ports. Yet during the course of interviews, multiple officials noted that levels of expertise and threat detection remain uneven across the region. Meanwhile, the sophistication of attacks is growing, with attackers increasingly able to bypass controls in sensitive networks. This adds pressure on countries to take an already long list of actions (one EU mapping exercise identified at least 72 basic security measures).

The fourth is calibration. Intensifying competition has sparked concerns among some Southeast Asian states that this may further tilt the balance of attention towards geopolitical dynamics at the expense of a wider range of non-traditional security challenges. One example where this calibration dynamic is evident is in the maritime agenda in ASEAN, since the grouping operates by consensus. Pressing agenda items previously pushed by forward-leaning countries like Singapore on underwater domain awareness (UDA) such as an underwater code and submarine safety portal had difficulty advancing due to sensitivities among certain states on US-China tensions as well as intra-regional mistrust. Meanwhile, the regional maritime agenda has increasingly resembled what one official called a “list approach” combining views of all countries rather than emphasizing a more focused approach. For example, the maritime pillar of the initial ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) acknowledged “potential for open conflict” and then went on to specify no less than 25 agenda items including awareness promotion. Some countries like Indonesia have since tried to better reflect geopolitical challenges into initiatives like the first-ever ASEAN Maritime Outlook and defense-related aspects of AOIP.

The fifth is contestation. Intensifying major power competition has complicated contestation inherent in the intraregional management of maritime disputes. A case in point is the South China Sea disputes, with five Southeast Asian states having conflicting claims with China (Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam consider themselves claimants, while Indonesia does not). Close US-China encounters have turned the South China Sea disputes into a superpower flashpoint. But they have also exposed the remaining progress Southeast Asian claimant states have to make in managing lingering maritime disputes among themselves, which can complicate ties in sensitive areas like illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) fishing or regional diplomacy. To take just one example of how regional unity remains elusive, Malaysia has lodged protests against both Vietnam’s island-building program and new Philippine maritime laws over contested claims, even though both actions were partly directed in response to Chinese actions. While there have been attempts at resolving bilateral maritime disputes, practitioners point out that successes are rare and glacial. One between Indonesia and the Philippines took around two decades; another between Indonesia and Vietnam took over a decade.

Policy Recommendations

Adjusting to the intersection between complex maritime challenges and intensifying major power competition will require actions from a range of actors, including institutions, regional states and key powers. For the US and its partners, efforts to adjust to these realities would ideally provide a foundation for countries to address challenges, respond to changing geopolitical shifts and reinforce an open and multipolar maritime order.

1. Advance underwater domain awareness. Forward-leaning Southeast Asian states should continue advancing a comprehensive underwater domain agenda despite challenges therein. Existing entry points such as critical underwater infrastructure (CUI) security and the defense uses of artificial intelligence should be seen as ways to create a broader regional floor within relevant forums such as the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting. Platforms like the ASEAN Coast Guard Forum can also be useful hubs to develop regional protocols and regularize interactions between law enforcement agencies. Beyond that, forward-leaning countries such as Singapore should find creative outlets to work with like-minded states in and beyond the Indo-Pacific on sensitive issues such as submarine safety which have previously encountered difficulty advancing in larger multilateral formats despite the gradual proliferation of submarines in the region.

2. Cultivate a comprehensive blue economy approach in the regional economic security agenda. Policymakers should sustain the cultivation of a comprehensive blue economy approach within economic security. This can help connect the maritime domain to national growth imperatives and address inclusivity and sustainability challenges. The trajectory in some areas like fisheries will have global relevance given that the region accounts for about a quarter of global fish production. Maintaining regional momentum will be important to build on previous advances led by countries like Indonesia that includes a blue economy framework. Emphasis should be placed on developing partnerships that emphasize building bankable projects and linkages with micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Past cases in point include the ASEAN Blue Economy Innovation Project with Japan and the United Nations, as well as the Blue SEA Finance Hub with the Asian Development Bank.

3. Accelerate the management of bilateral maritime differences. Relevant Southeast Asian states should accelerate the management of remaining bilateral and regional maritime differences. Apart from wider boundary negotiations, focus should be placed on tackling sensitive flashpoints like IUU fishing through mechanisms like hotlines as countries such as Vietnam have attempted despite continued challenges. Southeast Asian claimant states should also coordinate among themselves on individual resource management issues in the South China Sea, even if wider inter-claimant consensus proves elusive. Apart from progress on a code of conduct, select areas of cooperation on the ASEAN-China track such as scientific research should be pursued with what one regional official described as clear-eyed understanding of “dual-use risks”.

4. Strengthen coordination on MDA technology capacity-building. The US and its partners should work with Southeast Asian states to further facilitate MDA technology adoption and capacity-building. The focus should be on promoting “common desktop” approaches that help countries navigate the marketplace of proliferating MDA products and address concerns on duplication and compatibility. Multi-country or public-private partnerships should be considered to mitigate costs, reduce geopolitical sensitivities and empower local communities to utilize MDA technology for use cases like IUU fishing or environmental disasters. While these approaches will need to be tailored for each country, the Philippines offers one example of multi-country approaches such as Canada’s Dark Vessel Detection Program and the US SeaVision program.

5. Deepen strategic cooperation on critical maritime infrastructure. Regional and global actors and institutions should deepen cooperation on critical maritime infrastructure with Southeast Asian states given the region’s importance in this domain. Collaboration should adopt a comprehensive ecosystem approach that includes not only shipping, but also adjacent areas such as communications and energy. Pathways can include interagency maritime cybersecurity exercises and sharing best practices on subsea cables under discussion at forums such as the International Cable Protection Committee. Partners should also support regional strategic port assessments – including dry ports in cases like landlocked Laos – as advanced by actors such as Australia and the European Union. This will help maintain a more multipolar maritime order in the face of China’s increasingly dominant position as the world’s largest navy and a shipbuilding giant.

6. Build inclusive regional connections across the Indo-Pacific maritime agenda. Major powers should help build shared and inclusive connections between Southeast Asia priorities and the wider Indo-Pacific maritime agenda. One touchpoint is building out the maritime component of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP). The AOIP has aspects that connect with the initiatives of major powers like Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy and India’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative. Countries like Thailand and East Timor can play bridging roles due to their geographic position, including in cross-subregional initiatives in the Bay of Bengal and Coral Triangle Area respectively. Another is best practice sharing between institutions grouped as fusion centers despite variations. These include the Information Fusion Center in Singapore; the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency in the Solomon Islands; the Pacific Fusion Center in Vanuatu and the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Center in Madagascar.

Author

CEO and Founder, ASEAN Wonk Global, and Senior Columnist, The Diplomat

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more