Introduction

Indo-Pacific institutional development has been intensifying amid growing strategic competition. A rising China has rolled out new initiatives, Washington is building like-minded coalitions like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) faces challenges to its status as a hub for multilateral diplomacy. The dynamics this institutional flux produce is critical to the Indo-Pacific’s trajectory and US interests. The emerging Indo-Pacific institutional mix in the coming years will help shape norms, the balance of power and policy areas of US importance across core Indo-Pacific subregions such as the Indian Ocean, the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

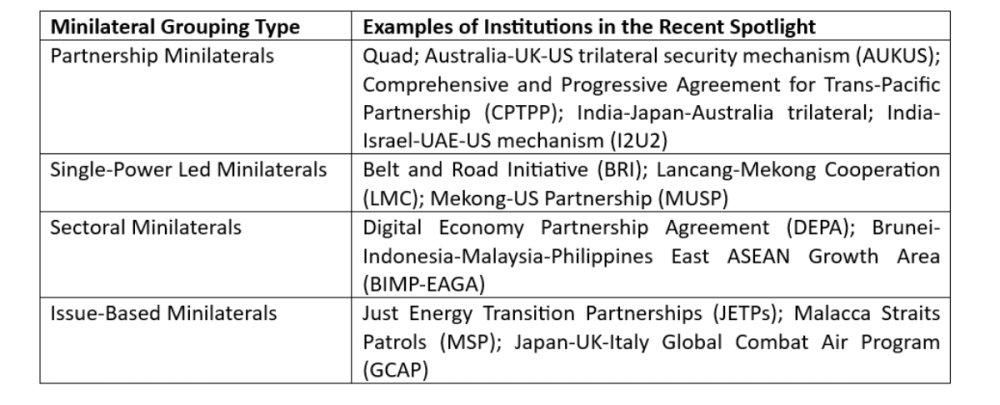

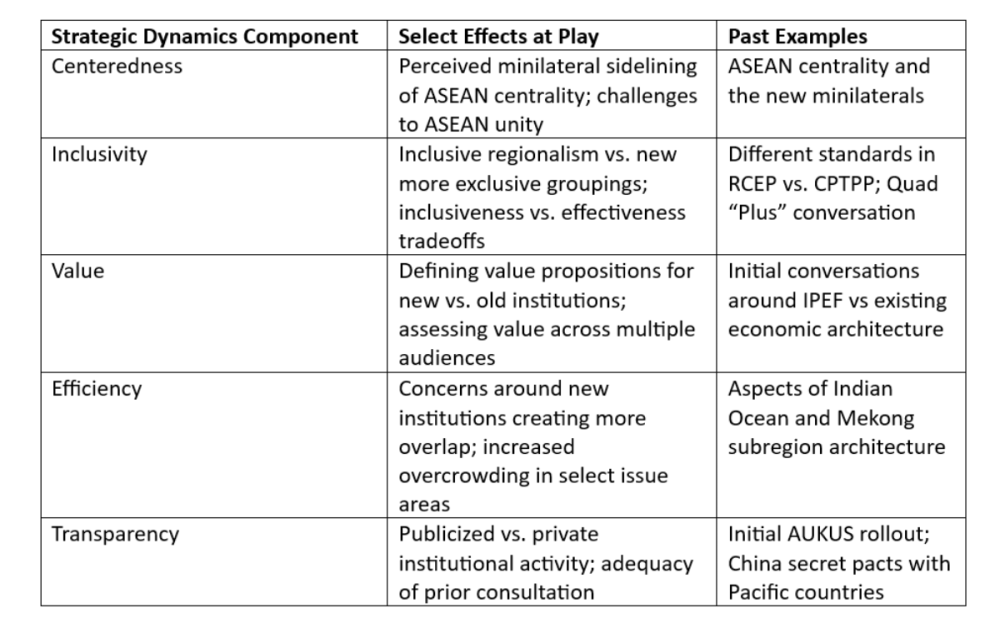

This policy brief explores the ongoing Indo-Pacific institutional flux and the opportunities and challenges it creates. It is informed by conversations with policymakers and experts across key Indo-Pacific capitals, including multiple trips across the region. The brief makes three main arguments. First, this period of Indo-Pacific institutional flux is notable for the increasing pressure on multilateralism, the formation of looser bilateral partnerships as well as several varieties of minilaterals. Four types of minilaterals are particularly evident: sectoral, partnership, major-power led and issue-based minilaterals. Second, these changes impact evolving dynamics in the institutional space. Five components are especially notable: centeredness; inclusivity; value; efficiency; and transparency. Third, actors, including regional states as well as the US and its partners, can help shape the direction of this Indo-Pacific institutional flux in ways that advance a shared vision of a free and open region.

Indo-Pacific Institutional Flux in Perspective

This period of Indo-Pacific institutional flux is just the latest we have seen over the decades. During the Cold War, Asian states formed indigenous groupings apart from the network of US alliances. This included ASEAN in Southeast Asia in 1967 or the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in South Asia in 1985. Some set up new institutions to accommodate balance of power shifts, with a case in point being the Five Power Defense Arrangements (FPDA) between Australia, Britain, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore in the face of British withdrawal from Southeast Asia. The post-Cold War period in the 1990s and into early 2000s saw greater impetus to utilize new institutions like the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) and the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) to pursue integration. Meanwhile, ASEAN cemented its role as an Indo-Pacific convenor by hosting annual leader meetings via the East Asia Summit (EAS) process. But periodic crises also revealed the limits of these new institutions. The clearest example of this in the early 2000s was the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which sparked the first iteration of the subsequently revived and recalibrated Quad.

The 2010s and 2020s have seen a period of Indo-Pacific institutional flux. This is characterized by greater pressures on multilateralism, proliferating minilaterals and bilateral partnerships as well as cementing of the Indo-Pacific strategic concept. Existing institutions like ASEAN are facing growing headwinds, while new groups are being created as countries seek more flexible cooperation amid a series of factors including erosion of aspects of the rules-based order; US-China competition; and the intensification of trends such as climate change and digitalization. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim of Malaysia, traditionally one of the Indo-Pacific’s most diplomatically active countries, has termed this an “age of flux”. The headlines around minilateral institutions tend to focus heavily on cases like the Australia-UK-US trilateral security mechanism (AUKUS). Beyond AUKUS or the Quad, countries apart from the US, including in Southeast Asia, are also pursuing minilateralism to address challenges more quickly and flexibly. This includes the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) kicked off between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore, or the Sulu Sea trilateral patrols between Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Beyond AUKUS or the Quad, countries apart from the US, including in Southeast Asia, are also pursuing minilateralism to address challenges more quickly and flexibly.

As it stands today, the minilateral label has been applied loosely to institutions of different types. These groupings exist alongside relatively newer bilateral and multilateral mechanisms. These include the EU-India Trade and Technology Council (TTC) established in 2021 or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) grouping ASEAN, Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea – the world’s largest free trade pact that entered into force in 2022. Some minilaterals, such as the Australia-India-Japan trilateral, India-Israel-UAE-US mechanism (I2U2) or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership CPTPP) in the trade space, are partnership minilaterals, with multiple countries working on issues across sectors. This is in contrast to minilaterals led by one power, as seen in the Mekong subregion in Southeast Asia with China’s Lancang Mekong Cooperation (LMC) or the Mekong-US Partnership (MUSP). Similarly, some minilaterals are focused around a specific sector. Examples here include DEPA and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Others have an even narrower focus. For example, the Malacca Straits Patrols (MSP) in place since the 2000s involve policing in the Malacca Straits, and Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) touch on energy and the environment. Despite these categorizations, institutions can overlap or move across them over time for various reasons. These include membership expansion, agenda shifts and changing leaderships.

Evolving Strategic Dynamics

This new period of Indo-Pacific institutional flux contributes to several strategic dynamics that affect calculations of key actors including ASEAN, China, the US and powers such as Australia, India and Japan. Dynamics are notable across five areas: centeredness; inclusivity; value; efficiency; and transparency. They add up to the acronym CIVET.

The first is around centeredness. Most notably, the challenges ASEAN faces as an institution, coupled with the consequences of minilaterals like the Quad and AUKUS, have intensified fears in ASEAN of loss of the grouping’s traditional “centrality”. This threatens to sideline an organization that is the Indo-Pacific’s default diplomatic convener even if it has fallen short on addressing challenges such as Myanmar or the South China Sea.

The second is around inclusivity. The growth of new US- and China-led institutions amid growing competition complicates the idealistic quest for open, inclusive regionalism. The US and its partners are spearheading more exclusive and like-minded groupings like AUKUS to address Beijing’s growing military capabilities in ways that multilateral fora cannot. Though China cries foul about containment, Beijing is building exclusive, China-led mechanisms to boost its influence. At times, this is done with the window dressing of “Asia for Asians” that one official described to the author as “China-first” with an “Asia -first disguise”. Beyond what it means for US interests, Beijing’s moves also raise concerns for other powers, be it India in the Indian Ocean or Australia in the Pacific. Periodic developments have spotlighted some of this, be it new China-led mechanisms on the Indian Ocean or aspects of Beijing’s agreements with the Pacific.

The third is around value. The birth of new institutions has intensified the value proposition challenge for existing and newer mechanisms alike. For instance, in the economic realm, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) has made select inroads in areas like supply chains. But it faced initial questions about its value proposition for lacking market access provisions. In the security realm, the Quad has been gradually clearer about its regional value proposition. The Quad’s efforts to support scholarships and establish working groups across shared priority areas like health and climate defined an agenda beyond just balancing China. Indeed, some survey data point to relatively greater support in regions like Southeast Asia for the Quad after initial skepticism.

The birth of new institutions has intensified the value proposition challenge for existing and newer mechanisms alike.

The fourth is around efficiency. The growth of institutions has intensified concerns around inefficiency caused by overlaps, duplication and siloing. Silos can hamper the performance of proliferating regional frameworks, with major powers having different conceptions of how this strategic space fits into their mind maps. The Mekong subregion is an example. There have been repeated calls within the region for limiting inefficiencies caused by duplication among the over dozen Mekong frameworks in place. These include those led by regional states like Thailand or by powers like Japan and South Korea. One senior official from a Mekong country described the institutional dilemma to the author as being caught between “overdominance” by China and “overcrowding” by institutional proliferation to further national interests and check Beijing’s rise.

The fifth is around transparency. This is often most referenced in the security realm, with cases including the perceived lack of adequacy in initial AUKUS consultations or the disclosure of China-driven secret regional agreements on police presence or naval facilities. But this applies to the economic realm too. For instance, original Trans-Pacific Partnership talks saw repeated requests for more transparency by legislatures and civil society actors in the US and among some other negotiating partners. This raises broader questions about the extent of transparency required as countries enter looser and more informal partnerships that may not require formal approval.

Policy Implications

Adjusting to this period of Indo-Pacific institutional flux will require actions from a range of actors including institutions, regional states and key powers. For the US and its partners, efforts to adjust to Indo-Pacific institutional flux would ideally both provide a foundation for countries to address shared challenges while also reinforcing a free, open and multipolar regional order rather than one dominated by China.

1. Shoring Up ASEAN

ASEAN is an indispensable part of sustainably adjusting to Indo-Pacific institutional flux as the region’s default convening hub for diplomacy. At a minimum, all Southeast Asian states must set a clear floor of commitment to ASEAN centrality that includes avoiding self-inflicted wounds, as we saw with the lack of a South China Sea joint statement in 2012. Preserving a semblance of unity is part of the “collective responsibility” of member states enshrined in the ASEAN Charter. More forward-leaning Southeast Asian states should push internal structural reforms to make ASEAN more responsive and flexible. Strengthening select institutions like the East Asia Summit would be a useful step to maintain major power interest in ASEAN, even if oft-discussed steps like a formal softening of consensus-based decision-making by expanding “ASEAN Minus X” arrangements prove difficult. Efforts should also be made to streamline institutional work and boost connectivity between ASEAN and minilaterals within Southeast Asia. Recent examples include the quest for greater institutional clarity in the maritime domain and more engagement with the Mekong River Commission.

“ASEAN is an indispensable part of sustainably adjusting to Indo-Pacific institutional flux as the region’s default convening hub for diplomacy.”

2. Strengthening Subregional Mechanisms and Connections to Regional Architecture

Other active states should strengthen subregional institutions and connect them to the wider regional architecture. The Pacific is a case in point, with the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent providing an indigenous longer-term subregional plan which major powers can dock on to rather than the agenda being externally-driven. In South Asia, India plays an important bridging role given its heft and connectivity potential with institutions in other parts of the region. These include the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and Mekong Ganga Cooperation Initiative (MGC) that connect New Delhi to Southeast Asia. More diplomatically active countries like Indonesia can play a role to advocate for more ASEAN engagement with other regional institutions to facilitate connectivity.

3. Managing New Institutional Development in a Context of US-China Competition

Both the US and China should be mindful of actions that can undermine institutional development as the Indo-Pacific’s two leading powers, be it China’s lack of transparency in its Pacific engagement or the initial US discouraging of certain partners to not join Beijing’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Other regional actors like ASEAN also have a role in setting out common principles for institutional development amid major power divergences.

4. Greater US Engagement in Regional “Variable Geometry”

The US should engage Indo-Pacific institutions sustainably with a narrative that balances creating new institutions and engaging with the existing architecture. This counters notions that Washington is undermining ASEAN centrality or dividing the region. For example, US officials could apply the articulation of “variable geometry” to describe its global approach to institutions to message US comprehensive institutional engagement in the Indo-Pacific. This narrative would go beyond security institutions like the Quad or AUKUS and highlight US economic institutional examples, such as the private partnership under the I2U2 or the new US-Singapore technology pact – which officials say Washington only currently has with three other countries in India, Israel and South Korea.

5. Entrenching a Shared Multipolar Vision in Institutional Development

Other major powers have a critical role to play in shaping the institutional agenda through an open, transparent, inclusive process that promotes a multipolar region. Examples include Australia’s socializing of AUKUS with the wider region after its initial mixed reception as well as Japan encouraging Washington to be more inclusive in searching for IPEF partners. Speaking out on the need for open regionalism can be helpful. One example referenced by regional interlocutors was Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s 2022 speech, where he warned that “Asia for Asians” conceptions pushed by Beijing can seem like “narrow Asian chauvinism.”

6. Linking Global Institutions to Regional Architecture

Regional and global actors and institutions can help boost connections with Indo-Pacific architecture. This would create more options for states amid greater calls for representation in parts of the Global South and expansion efforts by other institutions such as the BRICS. Cases in point include the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD’s) efforts to kickstart more Indo-Pacific country partnerships as well as the G-7 and G-20 being more representative about agendas and even adjusting membership as we have seen with the African Union.

Author

CEO and Founder, ASEAN Wonk Global, and Senior Columnist, The Diplomat

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Australia’s Deepening Ties with ASEAN Benefits America

How a Prabowo Foreign Policy Could Impact US-Indonesia Relations