Hezbollah, a Shiite movement in Lebanon, has evolved from a shadowy militia in the early 1980s to become a political powerbroker and the world’s most heavily armed non-state actor by four decades later. Fostered by Iran, it emerged after Israel’s 1982 invasion and amid the chaos of the Lebanese civil war, which broke out in 1975.

Since its formation, the “Party of God” has been armed, trained, and funded by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). It has also espoused Iran’s revolutionary ideology and its opposition to foreign influence, most notably the United States and the West. Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah has called Israel “an aggressive, illegal, and illegitimate entity, which has no future in our land. Its destiny is manifested in our motto: 'Death to Israel’,” he said in 2005. Hezbollah has pledged allegiance to Iran’s supreme leader but has downplayed establishing an Islamic state in Lebanon, which is home to 18 religious groups including four Muslim sects, 12 Christian sects, the Druze, and Jews.

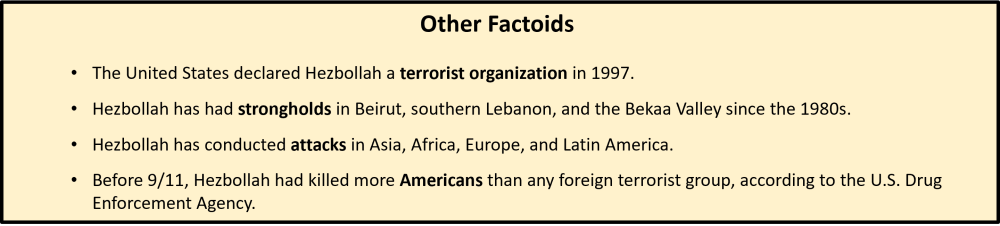

The group also cultivated a reputation as a defender of Lebanon’s Shiite minority and, more broadly, against Lebanon Israel’s military occupation. It assumed the mantle of chief resistance force against Israel and Western forces after the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was forced to withdraw from Lebanon in August 1982. Hezbollah’s campaign of suicide bombings against US and Israeli targets killed hundreds, a major factor in the Reagan administration decision to end the US peacekeeping mission to Lebanon in 1984 and Israeli forces to withdraw from Lebanon in 2000.

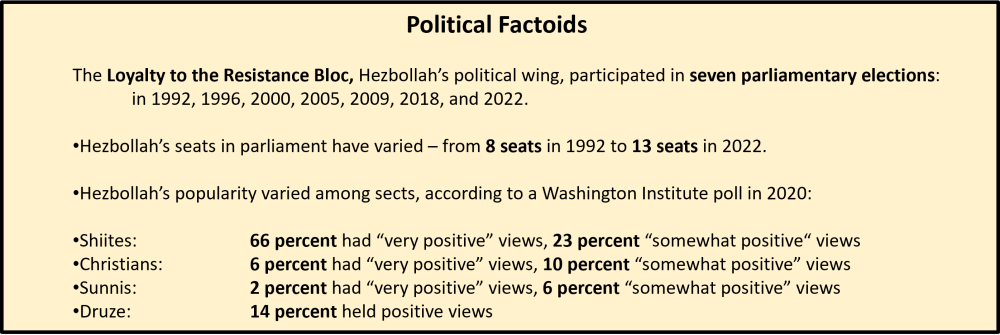

Hezbollah emerged as a political party in 1992, when it ran for elections. It grew in popularity by exploiting Shiite grievances over marginalization by Sunni and Christian political elites. It provided followers with better social services – including medical care, education, reconstruction assistance, and banking services – than the dysfunctional Lebanese state.

Hassan Nasrallah has been the secretary general since 1992. He has long had close relationships with Iranian leaders. In 2000, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei hosted Nasrallah in Tehran to congratulate him for Hezbollah’s role in pushing Israel to withdraw from Lebanon. Iranian top military officials and diplomats have frequently met him during visits to Beirut. Nasrallah was especially close to the late Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the elite Qods Force who was killed in a 2020 US drone strike.

History and Evolution

During its first phase, from 1982 to 1991, Hezbollah focused on defending Shiites amid the civil war and expelling Western and Israeli forces from Lebanon. In an 1985 open letter, Hezbollah declared its objectives, which included expelling Western forces from Lebanon, establishing an Islamic government in Lebanon, and destroying Israel. During phase two, from 1992 to 2000, Hezbollah started running in elections. It won eight seats and expanded its political influence. But the movement did not abandon its arms or the struggle against Israel. Its guerilla campaign, which killed more than 900 Israeli soldiers and eroded Israeli public support for the occupation of southern Lebanon.

Hezbollah’s third phase, from 2000 to 2005, was a tumultuous period. In May 2000, Israel voluntarily withdrew from southern Lebanon. It was the first time Israel unilaterally withdrew from Arab territory without concessions or a peace treaty. Claiming victory, Hezbollah earned respect from more Lebanese and Arabs across the Middle East. But Israel’s withdrawal also led some Lebanese to question whether Hezbollah had a right to keep its weapons, which all other Lebanese militias had agreed to surrender.

Lebanese politics was thrown into chaos in February 2005, when former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated by remote-control bomb detonated as his convoy passed by. The attack triggered nationwide protests against Syria—dubbed the Cedar Revolution, after the national tree-- that went on for more than two months. In April 2005, Syria withdrew its military forces after three decades of occupation. ad of the June 2005 parliamentary elections.

During the fourth phase, from 2006 to 2012, Hezbollah abducted two Israeli soldiers on July 12, which triggered an Israeli military response and a 34-day war. The war, which killed 1,100 Lebanese and more than 160 Israelis, ended in a military stalemate. Despite destruction costing billions, Hezbollah claimed a “divine victory.” Its popularity grew across the Middle East. “It was the first Arab army to ‘defeat’ Israel by not being destroyed,” Matthew Levitt, a fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told The Islamists. “People were impressed that it stuck a finger in Israel’s eye and lived to tell the tale.”

The fifth phase, from 2012 to 2019, was transformative for Hezbollah. In neighboring Syria, the Arab Spring protests in 2011 deteriorated into a civil war. Hezbollah initially deployed small contingents of fighters to protect Shiite villages in Syria along the border. Its intervention steadily escalated. By 2014, the Lebanese militia had thousands of fighters defending the Assad regime alongside Syrian forces, Iranian advisors, and Iraqi militias. Hezbollah’s popularity suffered due to its intervention against largely Sunni rebels in a predominantly Sunni region.

During the sixth phase, starting in 2019, Hezbollah faced overlapping domestic crises. The Lebanese suffered from skyrocketing prices as the value of the pound plummeted, unemployment soared, public services collapsed, and political elites were increasingly viewed as corrupt and/or inept. In October 2019, the government put a tax on the popular messaging platform WhatsApp, which triggered mass protests in Beirut. After anti-government demonstrations spread nationwide, Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned and Hassan Diab, a former education minister, was named to replace him. In early 2020, new anti-government protests spiraled into clashes with security forces outside parliament. The violence also pitted Hezbollah supporters and opponents as the flashpoints expanded to include Hezbollah’s vast arsenal. The protests lost momentum as COVID-19 spread.

Hezbollah faced new criticism after a massive explosion at the port—triggered by improper storage of ammonia nitrate--killed more than 200 and leveled part of East Beirut in August 2020. The government launched an investigation after many Lebanese held Hezbollah responsible for its role at the port. Nasrallah denied responsibility and accused the lead judge of using “the blood of the victims to serve political interests.”

Political Wing

Hezbollah’s political wing, the Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc, emerged as a key power broker in Lebanese politics after it first ran for office in the 1992 parliamentary elections. In seven elections between 1992 and 2022, it rallied the Shiite vote by offering extensive social services to followers. Beginning in 2005, it became part of the government by holding one to three government ministries. It further exercised influence through diverse political allies, including Christian politicians. In 2005, it became the dominant party—and glue—of the March 8 bloc that included Amal, (another Shiite Party), the Free Patriotic Movement, (the largest Christian party), and smaller Christian, Sunni, and Druze parties and independents. In January 2020, Prime Minister Diab formed the first government to be exclusively backed by Hezbollah’s parliamentary coalition. Diab’s cabinet reflected how far the Shiite party had come.

By 2023, Hezbollah was often described as a “state within a state” because it was part of the Lebanese parliament and government while also operating its own political, military and social services network with a great degree of impunity. Hezbollah is in government “to the extent that it directs resources towards its interests,” Levitt told The Islamists. “It can [also] prevent government decisions that are against its interests. But it is out of government to the extent that it’s not held accountable for what the government does or does not do, and it’s independently able to make decisions of war and peace, life and death, for the entirely of Lebanon – without consulting either the people or the government.”

Timeline of Political Events

1992: After a decade as an underground extremist movement, Hezbollah ran in the 1992 parliamentary elections for the first time. It won only eight seats in Lebanon’s 128-seat assembly, with four more independents considered to be in its bloc. Hezbollah outperformed 13 other parties. (Independents won the largest share.)

1996: Hezbollah won seven seats in the 1996 parliamentary election, with two more who ran as independents joining its bloc.

2000: Hezbollah won 10 seats, with two more seats going to independent allies, in the 2000 parliamentary election. The vote followed Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon after an 18-year occupation, during which Hezbollah was its primary adversary.

2005: Former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was murdered, which triggered the Cedar Revolution against the pro-Syrian government of Prime Minister Omar Karami and the Syrian troops in Lebanon. The government collapsed, and Syrian forces withdrew. In subsequent parliamentary elections, Hezbollah won 14 seats. It formed the March 8 Alliance with six other political parties, including Amal, a predominantly Shiite party, and the Free Patriotic Movement, a Christian party. Hezbollah joined the government for the first time. In a national unity government, Hezbollah members were appointed to be minister of labor and minister of energy and water.

2006: Months after the 34-day war between Hezbollah and Israel, the Shiite party withdrew from the Lebanese government over attempts to curtail its military and amid calls for a tribunal to investigate the Hariri assassination. Nasrallah called for nationwide protests. The political crisis, and sporadic pro- and anti-government protests, continued well into 2007.

2008: In July, Hezbollah joined a new unity government. It was appointed to lead the ministry of labor, but its political influence grew with allies awarded other ministries.

2009: In parliamentary elections after passage of a new law, Hezbollah won 13 seats. The other parties in the March 8 Alliance won 44 more. The Shiite party was appointed to lead the ministry of agriculture and ministry for administrative development.

2011: Hezbollah and its political allies from the unity government of Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned over an investigation by the international Special Tribunal for Lebanon, made up of UN-appointed judges, into the 2005 assassination of his father, former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. The resignation of 11 ministers in January toppled the government amid widespread expectations that Hezbollah would be implicated in the murder.

Later in January, lawmakers nominated tycoon Najib Mikati, a former prime minister and supported by Hezbollah, to be prime minister. Across Lebanon, thousands rallied against Mikati’s candidacy. Sunnis were angry that the Sunni post went to someone perceived as an ally of Shiites. In June, Mikati formed a new government composed of 30 ministers, 18 of whom were part of the Hezbollah-led March 8 Alliance. Hezbollah headed the ministry of state for administrative reform and the ministry of agriculture.

In July, the UN-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon announced the names of four Hezbollah militants indicted for the assassination of former Prime Minister Hariri. Nasrallah, a month earlier, had pledged to never allow Hezbollah members to be arrested in connection to the tribunal. “They cannot find them or arrest them in 30 days or 60 days, or in a year, two years, 30 years or 300 years,” he said.

2013: Prime Minister Mikati resigned after a contentious cabinet meeting. Hezbollah opposed creating a supervisory body for the upcoming parliamentary elections and extending the term of Major General Ashraf Rifi, the head of internal security forces. Hezbollah wanted Rifi, a Sunni, to retire on schedule the following month. Mikati’s resignation led to 10 months of political deadlock.

2014: In February, Prime Minister Tammam Salam announced a unity government of 24 ministers that included the Hezbollah-led March 8 Alliance, the Hariri-led March 14 Alliance, and independents. Each political bloc got eight portfolios, and the remaining eight went to independents. Hezbollah headed the ministry of industry and the ministry of state for parliamentary affairs.

In May, President Michel Suleiman’s six-year term came to an end. But lawmakers repeatedly failed to elect a successor amid sectarian violence. Sunni militants targeted Shiite areas and Hezbollah facilities because of the organization’s support for the Assad regime against largely Sunni rebels in Syria.

2016: After 29 months of political deadlock, Parliament elected Hezbollah ally Michel Aoun, a Christian, to be president in October. The election “shows new support for the Islamic resistance (against Israel),” Ali Akbar Velayati, a foreign policy adviser to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, declared. “This is surely a victory for Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of the Islamic Resistance in Lebanon.”

In December, Prime Minister Hariri announced a new 30-member unity cabinet with wide representation from political parties and sects. Hezbollah members headed the ministry of industry and the ministry of youth and sports. Amal, a Shiite party allied with Hezbollah, got three cabinet positions.

2017: Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri unexpectedly resigned in November. He blamed Iran and Hezbollah for destabilizing the region and stoking sectarian tensions. The Arab world would “cut off the hands that wickedly extend to it [Iran],” he warned. Hariri, a close ally of Iran’s rival Saudi Arabia, announced his decision from Riyadh on the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya satellite television station. Hariri accused Hezbollah of gaining power through its accumulation of weapons. Lebanon must have “only one state, one army, and one set of arms,” he said. Hariri also claimed that there was a plot on his life. He warned that the current political climate resembled that of 2005, when his father was assassinated. Hariri returned to Lebanon two weeks later. In December, Hariri reversed his decision to resign. He only returned to his post after Lebanese political factions pledged to not interfere in the affairs of other Arab countries.

2018: Hezbollah and its allies, including Shiite Amal and some Sunni and Christian groups, made large gains in the May 2018 parliamentary election. The bloc won a combined 71 seats, a majority. Hezbollah won 13 of the seats. “Today I can say that our goals have been achieved,” said Nasrallah.

2019: Prime Minister Hariri formed a new government in January 2019 after nine months of negotiations. The result was a national unity cabinet. Hezbollah members headed the ministry of parliamentary affairs and the ministry of youth and sports. A Shiite ally headed the health ministry. Hezbollah and its allies held a combined 19 out of 30 ministries.

In October, nationwide protests against elites and the sectarian political structure imposed since the end of the civil war in 1990 erupted. The demonstrations were sparked by a new tax on the popular messaging platform WhatsApp amid an economic crisis. Hezbollah and Amal supporters reportedly attacked protestors. Prime Minister Hariri resigned after nearly two weeks of protests. “We have reached a deadlock and we need a shock in order to brave through the crisis,” he said.

In December, Hezbollah and its allies in Parliament nominated Hassan Diab, a Hezbollah ally and former education minister, as prime minister. Thousands of people took to the streets to protest his selection because he was seen as member of the corrupt political elite.

2020: Prime Minister Diab formed a new government in January. It was the first government to be exclusively backed by Hezbollah and its allies. The 20-person cabinet included two politicians nominated by Hezbollah, the minister of industry and the minister of health. Prime Minister Diab, President Aoun, and Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri were also longstanding allies of Hezbollah.

On August 4, nearly 3,000 tons of improperly stored ammonium nitrate exploded at Beirut Port. Some members of the public implicated Hezbollah because it controlled part of the port. Rioting broke out due to anger over the explosion, which killed some 220 people, as well as the devaluation of Lebanon’s currency, and the impact of COVID-19. Hezbollah tried to quash an independent investigation and intimidate the judge in charge of the probe. Prime Minister Diab resigned less than a week after the Beirut blast due to public anger at the government.

2021: After a year without a fully functioning government, Prime Minister Mikati formed a new government in September. It was composed of 24 ministers, including 16 from the Hezbollah led-March 8 Alliance. Hezbollah headed the ministry of public works and the ministry of labor.

Nasrallah met with Ismail Haniyeh, the chief of the political bureau of Hamas, a Palestinian militant group sponsored by Iran. Haniyeh had not traveled to Lebanon for 27 years. The two discussed the 11-day conflict between Israel and Hamas in May.

2022: Hezbollah and its allies won 62 seats in the May parliamentary election. They fell short of the 65 seats needed for a majority. Voters fed up with the political establishment elected more than a dozen independent candidates. But Hezbollah maintained its 13 seats. And its ally, Berri, won his reelection bid for parliamentary speaker. Prime Minister-designate Mikati failed to form a new cabinet.

In June, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon sentenced Hezbollah members Hassan Habib Merhi and Hussein Hassan Oneissi to life imprisonment in absentia for Hariri’s murder in 2005.

President Aoun ended his six-year term in October. Parliament repeatedly failed to elect his replacement. A caretaker government with limited powers was charged with running the state. As of October 2023, Lebanon still did not have a president despite 12 rounds of voting.

Military Wing

Iran fostered and facilitated the embryo of Hezbollah after dispatching some 1,500 IRGC trainers and advisers to Lebanon’s eastern Bekaa Valley in 1982. The Iranians did not fight Israeli forces, but they mobilized, trained, funded and equipped a new underground militia in Lebanon that evolved into Hezbollah. The early cells attracted Shiites in southern Lebanon as well as the poor southern suburbs, known as the Dahiyeh, in Beirut.

In its early years, Hezbollah launched attacks against Israeli and Western forces—including the US-led Multinational peacekeepers — deployed in Lebanon. Its guerrilla tactics, including suicide bombings, were effective enough to eventually push Israel to withdraw in 2000 but were largely crude.

Hezbollah’s performance in the 2006 war with Israel marked a turning point for its military capabilities. It applied new tactics that surprised Israel. Hezbollah fired at least 3,900 rockets at Israel during the 34-day conflict. It also launched at least three drones at strategic sites in Israel and rammed an explosive-carrying drone into an Israeli warship. Hezbollah had also hardened its defenses and trained its fighters in a more disciplined way than before. “Today we can say proudly that if any Israeli government decides to launch war in the future, it will take into consideration that war with Lebanon will not be a picnic,” Nasrallah said in August 2006.

By 2023, Hezbollah had evolved into a militia more capable than many armies in the Middle East. It had four decades of operational experience both inside Lebanon and elsewhere in the Middle East, especially Syria. It accumulated a diverse arsenal of weapons, largely with the assistance of Iran.

Notable Abductions & Attacks

Hezbollah is linked to the bombings of two US embassies in Lebanon as well as the bombings of the US and French embassies in Kuwait. Its suicide bombing of the US Marine peacekeepers in Beirut in 1983 resulted in the largest loss to the US military in a single incident since Iwo Jima in World War II. Between 1982 and 1992, Hezbollah was responsible for abducting at least 44 hostages, including 17 Americans, according to a 1994 FBI report. Three Americans died in Hezbollah captivity. The following are major attacks by Hezbollah operatives.

July 1982: Gunmen kidnapped David Dodge, the acting president of the American University of Beirut. He was the only hostage imprisoned in Iran. He was released through Syrian intervention exactly one year later.

April 1983: Hezbollah was held responsible for the suicide bombing of the US Embassy in Beirut that killed 63 people.

October 1983: Hezbollah operatives bombed the separate compounds of US and French peacekeepers in Beirut, killing 241 Americans and 58 French.

January 1984: Hezbollah was blamed for the murder of Malcolm Kerr, the president of the American University of Beirut, on his way to work.

March 1984: The Shiite militia abducted William Buckley, the CIA Station Chief, in Beirut. He was interrogated, tortured, and ultimately died in captivity.

September 1984: Hezbollah bombed the US Embassy Beirut Annex, killing 23.

March 1985: Hezbollah militants abducted Terry Anderson, an Associated Press correspondent. He was held for seven years.

February 1988: Hezbollah abducted Colonel William Higgins, a UN peacekeeper. He was interrogated, tortured, and killed.

March 1992: Hezbollah was held responsible for a suicide bombing at the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, Argentina that killed 20 and injured 252.

July 1994: A Hezbollah militant detonated a car bomb at the Israeli embassy in London.

June 1996: Hezbollah was implicated in the truck bombing at Khobar Towers, a US Air Force housing complex in Saudi Arabia. The attack killed 19 service members and injured 500.

February 2005: Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri was assassinated in a car bombing. A UN tribunal implicated a senior Hezbollah commander and others in Hariri’s death.

July 2006: Hezbollah abducted two Israeli soldiers, which prompted a 34-day war with Israel. More than 1,000 Lebanese and 50 Israelis died during the conflict.

May 2008: Hezbollah operatives plotted a bomb attack against the Israeli embassy in Baku, Azerbaijan but it was foiled by Azerbaijani authorities.

February 2012: Israeli embassy personnel were reportedly targeted in coordinated bombing attempts in New Delhi, India and Tbilisi, Georgia. “In all these cases, the elements behind the attacks were Iran and its proxy, Hezbollah,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said.

July 2012: A suicide bombing at Sarafovo Airport in Burgas, Bulgaria killed six Israeli tourists and a Bulgarian bus driver. Israel and the European Union blamed Hezbollah.

October 2023: Dozens of Hezbollah fighters reportedly died in clashes with Israeli forces along the border in the weeks following the unprecedented attack on Israel by Hamas on October 7.

Iran Ties and Regional Activities

Since 1982, Hezbollah has embodied Iran’s grand strategy to create a network of proxy forces across the Middle East, both to expand Tehran’s sphere of influence and promote its security interests and Islamic ideology. Iran took advantage of centuries-old links to the Shiites of Lebanon. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the Safavid dynasty gradually converted Iran, a predominantly Sunni country, to Shiism. The Safavids enlisted the help of Shiite clerics from southern Lebanon. Subsequently, many Lebanese clerics studied in Iran and families intermarried. And many Iranians opposed to the shah sought refuge in Lebanon in the years leading up to the 1979 revolution.

Hezbollah’s first manifesto, issued in 1985, mirrored Iran’s ideology based on a revolutionary interpretation of Shiism. Iran’s influence has also been apparent in the organization’s logo, which includes a bare hand holding up a rifle and a globe, similar to the IRGC’s logo.

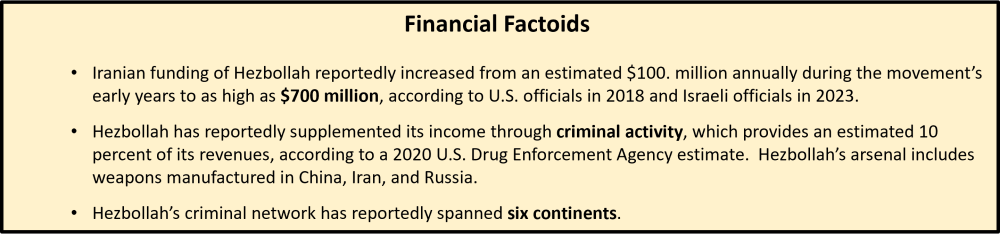

Tehran’s financial support for Hezbollah has fluctuated. In early 2009, Iran was reportedly forced to cut its funding to the group by 40 percent due to biting international sanctions over its controversial nuclear program and plummeting oil prices. In 2010, the United States estimated that Iran provided the group with between $100 million and $200 million per year.

Hezbollah’s “budget, everything it eats and drinks, its weapons and rockets, comes from the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Nasrallah said in 2016. In 2018, the Treasury Department estimated that Tehran provided Hezbollah with more than $700 million annually. In 2020, Iranian funding reportedly decreased due to the reimposition of US sanctions, declining oil prices and the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Iran played a key role in convincing Hezbollah to intervene in the Syrian civil war, which broke out in 2011. Nasrallah hesitated to deploy Hezbollah fighters to Syria at the IRGC’s request but reportedly relented due to a request from Supreme Leader Khamenei. At first, Hezbollah deployed to protect Shiite villages in Syria near the border but denied involvement in the conflict despite widespread reports to the contrary. In April 2013, Nasrallah finally acknowledged that Hezbollah was helping the Assad regime, also a key ally of Iran, fight rebels and Sunni extremists. “Syria has real friends in the region, and the world that will not let Syria fall in the hands of America, Israel or takfiri (extreme jihadi) groups,” he said in a televised speech.

In subsequent years, Hezbollah participated in key battles alongside Syrian forces, Iranian advisors and Iraqi militias. By 2018, it had reportedly lost 1,000 to 2,000 fighters in Syria. But it also gained valuable battlefield experience and attempted to entrench itself in Syria, especially along the border with Israel. Hezbollah has also reportedly trained other Iranian proxies in Iraq and the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

With the help of shipments from Iran, Hezbollah has grown its rocket and missile arsenal. Since 2016, Iran has reportedly provided conversion kits to upgrade Hezbollah’s arsenal from short-range rockets to precision-guided missiles capable of hitting deep into Israel. The suitcase-sized kits can add a GPS navigation and guidance system that increases the Zelzal-2 rocket’s accuracy and range to 300 km, or 185 miles. Engineers can reportedly convert a Zelzal-2 in two to three hours; the cost of converting an imprecise rocket into a guided missile costs between $5,000 and $10,000. Between 2016 and 2019, Hezbollah converted between 20 and 200 missiles, the Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre estimated.

Israel has accused the IRGC of supplying Hezbollah with the kits. In 2018, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu presented evidence that Hezbollah had allegedly set up three missile conversion plants near Beirut International Airport with Iranian help. In 2022, Nasrallah boasted that Hezbollah could convert rockets into missiles and produce drones in Lebanon.

Iran’s Qods Force, the arm of the IRGC responsible for external operations, has also reportedly helped establish a cyber unit in Hezbollah. Hacking groups linked to Hezbollah have reportedly infiltrated telecommunications companies in the United States, Europe and the Middle East. In 2022, Israel alleged that Iran, in cooperation with Hezbollah, launched a cyber operation to steal materials from the UN peacekeeping mission stationed in southern Lebanon near the Israeli border.

Timeline of Hezbollah-Iran Relations

June 6, 1982: Israel invaded Lebanon in Operation Peace for Galilee. Within weeks, Iran deployed 1,500 IRGC advisers to Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley to recruit, train and a new Shiite militia that evolved into Hezbollah.

April 18, 1983: Members of the nascent Hezbollah bombed the US Embassy in West Beirut, killing 63.

Oct. 23, 1983: Members of nascent Hezbollah bombed US and French peacekeepers in Beirut, killing 241 Americans and 58 French.

Dec. 12, 1983: Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for six coordinated bombings in Kuwait City that targeted the US and French embassies, the international airport, oil facilities, and Raytheon.

Sept. 20, 1984: Hezbollah bombed the second US Embassy Annex in East Beirut, killing 23.

June 14-30, 1985: Hezbollah hijacked TWA Flight 847 flying from Greece to Rome. It demanded that Israel release of 700 Shiite Muslims. The hijackers killed a US Navy diver and threatened to kill Jewish passengers. Iran provided logistical support to the hijackers, according to the National Counterterrorism Center.

March 17, 1992: Islamic Jihad, an organization linked to Hezbollah, claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing outside the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, Argentina that killed 20 and injured 252. An Israeli investigation in 2003 concluded that “the highest levels of the Iranian regime… had in fact authorized Hezbollah to carry it out.”

July 18, 1994: Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for an explosion outside the Argentine-Israeli Mutual Association in Buenos Aires that killed 95 killed and wounded 200. Argentine intelligence concluded in 2004 that a 21-year Hezbollah operative carried out the attack with Iranian logistical support. The bombing was the deadliest terrorist attack conducted in Argentina. In 2006, Argentine authorities issued an international arrest warrant for Ali Fallahian, head of Iranian intelligence, for orchestrating the operation. In 2007, INTERPOL placed Ali Fallahian, four other Iranian officials, and one Hezbollah member on its most wanted list for their alleged involvement in the bombing.

May 17, 1995: Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei appointed Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah and Shura Council member Mohammad Yazbek to be his religious representatives in Lebanon.

June 25, 1996: The bombers detonated a truck packed with 5,000 pounds of explosions parked near Khobar Towers, a US Air Force housing complex in eastern Saudi Arabia, that killed 19 service members and injured 500. Hezbollah al Hejaz, an Iranian proxy in Saudi Arabia, claimed responsibility. In 2001, a US federal grand jury chose not to indict any Iranians for the attack but alleged that “an Iranian military officer” directed the operation. In December 2006, a US federal judge ruled that Iran was responsible for the bombing and ordered the government to pay $254 million to the families of the Americans who died in the attack.

Aug. 1, 2005: Nasrallah met with Supreme Leader Khamenei and President Ahmadinejad in Tehran.

Jan. 20, 2006: Nasrallah visited Damascus, Syria, where he met with Iranian President Ahmadinejad.

May 2008: Hezbollah operatives plotted a bomb attack against the Israeli embassy in Baku, Azerbaijan but it was foiled by Azerbaijani authorities, who later claimed that the IRGC ordered attacks against US, Israeli and other Western embassies. It arrested 22 Azerbaijanis for allegedly training to be Iranian agents.

Feb. 26, 2010: Syrian President Bashar al Assad hosted Iranian President Ahmadinejad and Nasrallah.

Oct. 13-14, 2010: President Ahmadinejad visited Lebanon. “The whole world knows that the Zionists are going to disappear,” Ahmadinejad told Hezbollah in Bint Jbeil. He also met Nasrallah.

Dec. 16, 2010: Iran reportedly cut funding to Hezbollah by 40 percent due to biting international sanctions on Tehran over its controversial nuclear program.

Feb. 7, 2012: Nasrallah acknowledged that Hezbollah had received “moral, and political and material support in all possible forms” from Iran since 1982. “In the past, we used to tell half the story and stay silent on the other half,” he said in a speech. “When they asked us about the material and financial and military support we were silent.” He denied US allegations that Hezbollah laundered money and smuggled drugs, claiming that Iran satisfied the movement’s financial needs.

Feb. 13, 2012: Israeli embassy personnel were reportedly targeted in coordinated bombing attempts in New Delhi, India and Tbilisi, Georgia. In India, a motorcyclist planted a sticky bomb on an Israeli embassy minivan. In Georgia, a bomb was placed on an Israeli car but it failed to detonate. Israeli officials said the operations appeared to be directed by Tehran. “In all these cases, the elements behind the attacks were Iran and its proxy, Hezbollah,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said.

July 18, 2012: A suicide bombing at Sarafovo Airport in Burgas, Bulgaria killed six Israeli tourists and a Bulgarian bus driver. Israel blamed Hezbollah and Iran for the attack.

Oct. 11, 2012: Nasrallah confirmed that Hezbollah had flown a drone 25 miles into Israel on October 6. “It penetrated the enemy’s iron procedures and entered occupied southern Palestine,” he said. Israeli forces shot down the aircraft. Nasrallah boasted that the drone’s components were from Iran but that the drone had been assembled in Lebanon.

May 25, 2013: For the first time, Nasrallah confirmed that Hezbollah forces were fighting in Syria on behalf of the Assad regime. “Syria is the backbone of the resistance (in the region) and its main supporter,” he said in a speech. “If the armed groups (rebels) control Syria or specific Syrian provinces, especially those on the Lebanese border, then we consider them a great threat to Lebanon, the unity of the nation and all Lebanese, not just Hezbollah or Shiites in Lebanon.” Hezbollah subsequently deployed thousands of fighters in various parts of Syria. At least 1,300 Hezbollah fighters were killed and another 5,000 fighting rebels, including Islamic State militants, by 2015.

Nov. 22, 2014: Brig. Gen. Sayed Majid Moussavi, an IRGC general, claimed that Iran had provided Hezbollah with Fateh missiles capable of reaching any target in Israel, including the nuclear reactor in southern Dimona. The missiles had a range of 350 kilometers (217 miles) and could carry a 500 kg (1100 pounds). Naim Qassem, the Hezbollah deputy secretary general, said the Israelis “are well aware that Hezbollah is in possession of missiles with pinpoint accuracy, and thanks to the equipment Hezbollah acquired, and with the Islamic Republic’s support and Hezbollah’s readiness for any future war, [the next] war will be much tougher for the Israelis.”

Jan. 18, 2015: An Israeli airstrike killed Mohammad Ali Allah-Dadi, an IRGC general, and six Hezbollah fighters in Syria’s Golan Heights.

Dec. 22, 2016: Hezbollah fighters reportedly played a key role when Syrian forces defeated rebels, a decisive battle in Syria’s civil war.

Sept. 3, 2019: With Iranian support, Hezbollah was reportedly building a facility to “convert and manufacture precision-guided missiles” in the Bekaa Valley, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) claimed.

Jan. 5, 2020: Nasrallah pledged to push US forces out of the Middle East to avenge the US assassination of Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s elite Qods Force, in Baghdad. “All of us in our region and in our nation should seek just retribution,” he said.

Feb. 9, 2022: Nasrallah said that Iran was “a strong regional state and any war with it will blow up the entire region.” But he denied accusations that Hezbollah automatically took orders from Tehran. “Tell us about a single act that Hezbollah did for the sake of Iran rather than for the sake of Lebanon.” Hezbollah, he said, would not necessarily attack Israel in response to a strike on Iran.

Oct. 23, 2022: Over years, Israel had reportedly destroyed some 90 percent of Iran’s military infrastructure in Syria.

Sept. 11, 2023: Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant claimed that Iran was building an airport in southern Lebanon – just 12 miles from the Israeli border – that could be used to launch attacks. Iran “is planning to act against the citizens of Israel,” he said.

Oct. 12, 2023: Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian met Nasrallah in Beirut to confer on the war between Hamas and Israel. Israel had launched extensive airstrikes on the Gaza strip in response to an unprecedented attack by Hamas and Islamic Jihad that included infiltration into Israeli border communities, murders of civilians and kidnappings. Hezbollah “is in excellent condition and in full readiness to respond to criminal acts by the Zionist entity,” Amir-Abdollahian said after the meeting.

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

What Trump’s 2025 Inauguration Speech Says About US-Mexico Policy